What Happens During Anaesthesia?

How does anaesthesia work?

Anaesthesia works by using chemicals that act on the brain to induce a temporary state of enforced unconsciousness. During anaesthesia, your pet is unable to move and does not feel pain or other unpleasant sensations. It is generally used in the following situations:

- Procedures that involve significant pain or unpleasant sensations, such as surgery, dental scaling and extractions.

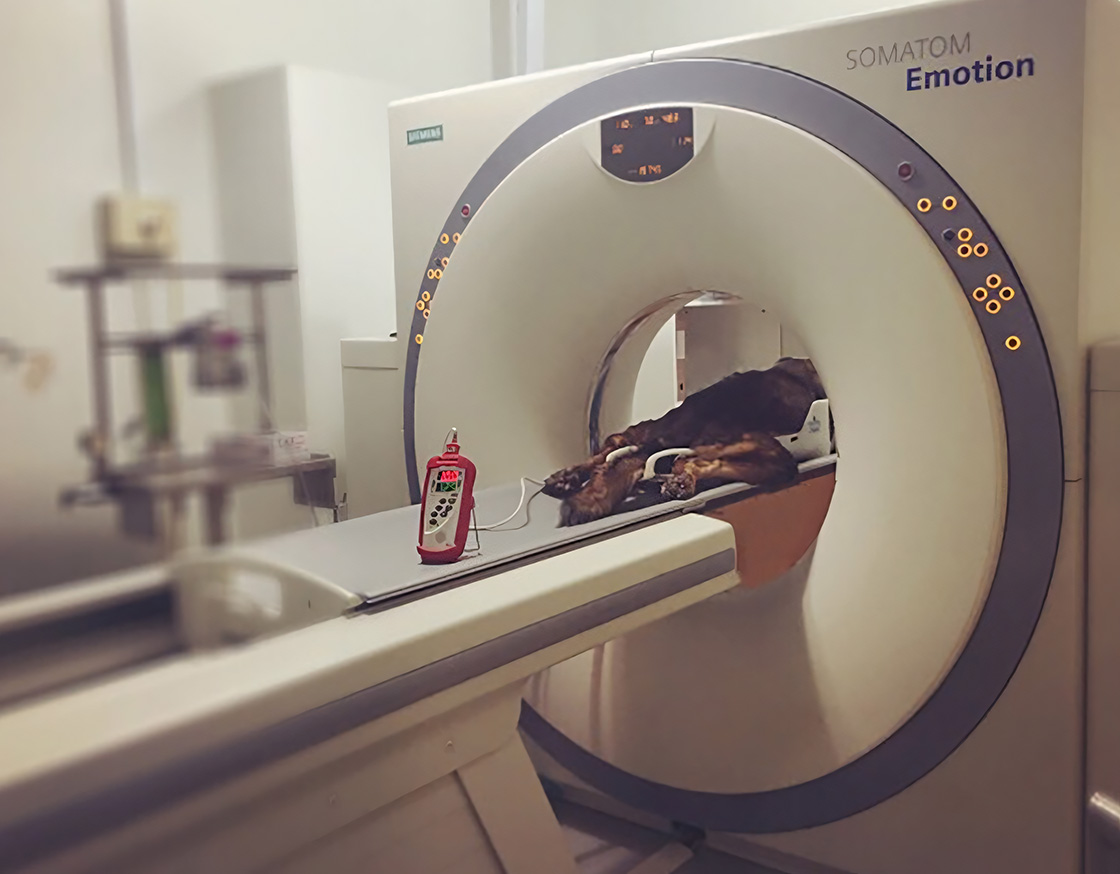

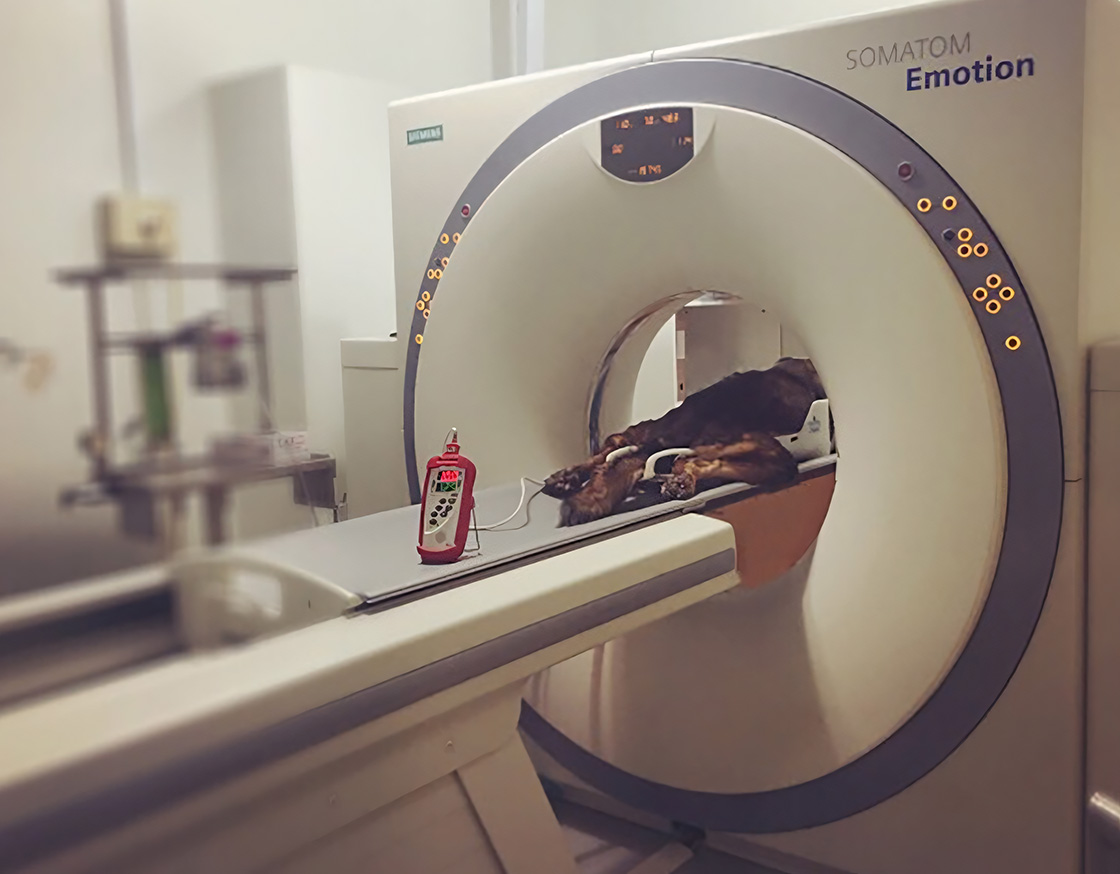

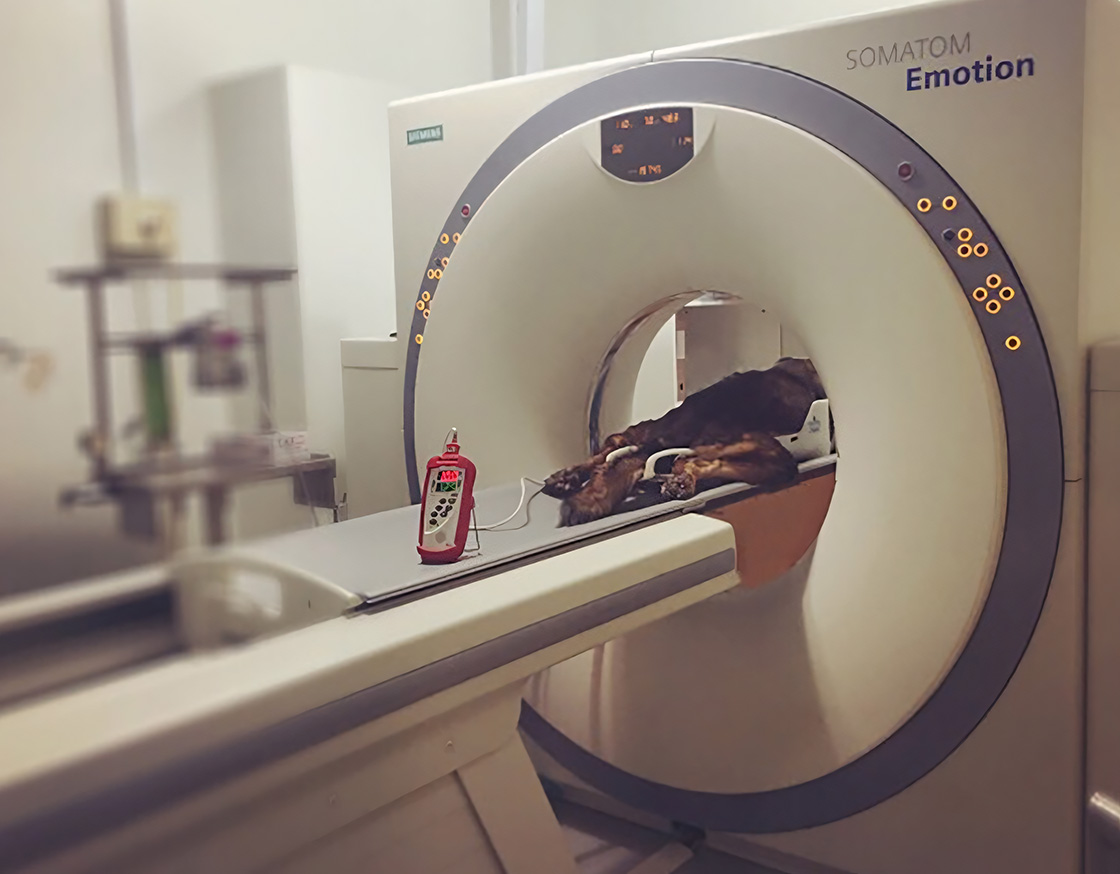

- The animal is nervous or uncooperative and is required to remain very still for procedures such as X-rays, MRI, CT scans.

- Occasionally for ear cleaning (especially if the ears are very badly infected).

- To manage repetitive, uncontrollable seizures or heavy breathing leading to collapse of the windpipe.

Key factors that affect anaesthesia risk

- Nature of procedure: Invasive procedures (open surgery) carry a higher risk than non-invasive procedures (e.g. dental cleaning).

- Length of procedure: The longer the procedure, the higher the risk.

- Age: The older the animal, the greater the anaesthetic risk because there may be pre-existing conditions of the heart, lung, liver or kidney. Animals below 1 year of age have a slightly higher anaesthesia risk as their organs may not be fully developed.

- Health status: The healthier the animal, the lower the anaesthetic risk. Animals with pre-existing health problems (such as heart conditions) face greater anaesthetic risk.

- Breed: Brachycephalic (flat-faced) breeds such as the Pug, Bulldog, Pekingese have structural problems with the nasopharynx which make breathing more difficult when they are asleep and completely relaxed.

What can be done to minimise the risk?

1. Pre-anaesthetic exam and blood tests

A thorough medical history provides valuable information about your pet’s health. Physical exam may reveal abnormalities of the heart or lungs which may require further evaluation such as an electrocardiogram, chest X-rays or ultrasound prior to surgery. Pre-anaesthetic blood tests are important to check blood glucose, kidney and liver function and screen for pre-existing health issues, especially in older pets.

- Complete blood count: To ensure there is no ongoing infection and to check the level of red blood cells and platelets, which are important in blood clotting.

- Kidney & liver function tests: The kidney and liver are organs which process the anaesthetic drugs, so it is important they are functioning properly.

- Heartworm & tick fever tests: Heartworm, which may not be detected on physical examination in early stages, can affect the heart’s ability to withstand stress, especially during surgery. Tick fever can affect blood clotting, which will greatly increase the amount of blood loss during surgery.

2. Intravenous fluids

For older animals with a higher anaesthesia risk or undergoing longer procedures, your vet may include intravenous (IV) drip to help your pet maintain hydration and blood pressure, process anaesthetic drugs faster and provide a convenient route for vets to administer fluids and medication into the bloodstream.

3. Airway intubation

A soft plastic tube (endotracheal or ET tube) is inserted into the windpipe to maintain the airway for breathing. This is connected to an anaesthesia machine that delivers an inhalant anaesthetic in oxygen. It allows our vet to assist or control breathing if it becomes necessary.

* Fasting your pet for several hours prior to anaesthesia (as directed by your vet) is important. A your pet who is not properly fasted could vomit during or shortly after being anaesthetised and possibly aspirate food or fluid into the lungs. Aspiration pneumonia can be life-threatening.

4. Anaesthetic monitoring

The number one cause of anaesthetic complications leading to death is cellular hypoxia – cells are starved of oxygen. Our patient’s vital signs such as heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, blood oxygenation are continuously monitored throughout the anaesthetic procedure.

Staying warm during and after surgery

Patients often experience hypothermia (reduced body temperature) during anaesthesia. Body temperature may be further reduced with the use of intravenous fluids, clipping of fur and surgical preparation. Warming pads are routinely used during anaesthesia to keep our patients warm. Anaesthetic monitoring constantly measures the body temperature during surgery.

Pain management – rest better and recover faster

Pain management is crucial as it alleviates discomfort and helps our animals recover faster. Pain relief medication is usually administered before, during and after surgery. This helps reduce stress and pain associated with surgery, allowing the animal to rest better and recover faster. It is always better to start on pre-emptive analgesia than to control pain once it has started.

With appropriate pre-anaesthesia examination, careful monitoring and competent after-care, the risks of anaesthesia can be minimised. Most animals are back to their normal selves within 12 to 24 hours. If your pet does not fully recover from the anaesthetic by the following day, contact your vet immediately.

Dr Kasey Tan, Mount Pleasant Animal Clinic (North)

How does anaesthesia work?

Anaesthesia works by using chemicals that act on the brain to induce a temporary state of enforced unconsciousness. During anaesthesia, your pet is unable to move and does not feel pain or other unpleasant sensations. It is generally used in the following situations:

- Procedures that involve significant pain or unpleasant sensations, such as surgery, dental scaling and extractions.

- The animal is nervous or uncooperative and is required to remain very still for procedures such as X-rays, MRI, CT scans.

- Occasionally for ear cleaning (especially if the ears are very badly infected).

- To manage repetitive, uncontrollable seizures or heavy breathing leading to collapse of the windpipe.

Key factors that affect anaesthesia risk

- Nature of procedure: Invasive procedures (open surgery) carry a higher risk than non-invasive procedures (e.g. dental cleaning).

- Length of procedure: The longer the procedure, the higher the risk.

- Age: The older the animal, the greater the anaesthetic risk because there may be pre-existing conditions of the heart, lung, liver or kidney. Animals below 1 year of age have a slightly higher anaesthesia risk as their organs may not be fully developed.

- Health status: The healthier the animal, the lower the anaesthetic risk. Animals with pre-existing health problems (such as heart conditions) face greater anaesthetic risk.

- Breed: Brachycephalic (flat-faced) breeds such as the Pug, Bulldog, Pekingese have structural problems with the nasopharynx which make breathing more difficult when they are asleep and completely relaxed.

What can be done to minimise the risk?

1. Pre-anaesthetic exam and blood tests

A thorough medical history provides valuable information about your pet’s health. Physical exam may reveal abnormalities of the heart or lungs which may require further evaluation such as an electrocardiogram, chest X-rays or ultrasound prior to surgery. Pre-anaesthetic blood tests are important to check blood glucose, kidney and liver function and screen for pre-existing health issues, especially in older pets.

- Complete blood count: To ensure there is no ongoing infection and to check the level of red blood cells and platelets, which are important in blood clotting.

- Kidney & liver function tests: The kidney and liver are organs which process the anaesthetic drugs, so it is important they are functioning properly.

- Heartworm & tick fever tests: Heartworm, which may not be detected on physical examination in early stages, can affect the heart’s ability to withstand stress, especially during surgery. Tick fever can affect blood clotting, which will greatly increase the amount of blood loss during surgery.

2. Intravenous fluids

For older animals with a higher anaesthesia risk or undergoing longer procedures, your vet may include intravenous (IV) drip to help your pet maintain hydration and blood pressure, process anaesthetic drugs faster and provide a convenient route for vets to administer fluids and medication into the bloodstream.

3. Airway intubation

A soft plastic tube (endotracheal or ET tube) is inserted into the windpipe to maintain the airway for breathing. This is connected to an anaesthesia machine that delivers an inhalant anaesthetic in oxygen. It allows our vet to assist or control breathing if it becomes necessary.

* Fasting your pet for several hours prior to anaesthesia (as directed by your vet) is important. A your pet who is not properly fasted could vomit during or shortly after being anaesthetised and possibly aspirate food or fluid into the lungs. Aspiration pneumonia can be life-threatening.

4. Anaesthetic monitoring

The number one cause of anaesthetic complications leading to death is cellular hypoxia – cells are starved of oxygen. Our patient’s vital signs such as heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, blood oxygenation are continuously monitored throughout the anaesthetic procedure.

Staying warm during and after surgery

Patients often experience hypothermia (reduced body temperature) during anaesthesia. Body temperature may be further reduced with the use of intravenous fluids, clipping of fur and surgical preparation. Warming pads are routinely used during anaesthesia to keep our patients warm. Anaesthetic monitoring constantly measures the body temperature during surgery.

Pain management – rest better and recover faster

Pain management is crucial as it alleviates discomfort and helps our animals recover faster. Pain relief medication is usually administered before, during and after surgery. This helps reduce stress and pain associated with surgery, allowing the animal to rest better and recover faster. It is always better to start on pre-emptive analgesia than to control pain once it has started.

With appropriate pre-anaesthesia examination, careful monitoring and competent after-care, the risks of anaesthesia can be minimised. Most animals are back to their normal selves within 12 to 24 hours. If your pet does not fully recover from the anaesthetic by the following day, contact your vet immediately.

Dr Kasey Tan, Mount Pleasant Animal Clinic (North)

How does anaesthesia work?

Anaesthesia works by using chemicals that act on the brain to induce a temporary state of enforced unconsciousness. During anaesthesia, your pet is unable to move and does not feel pain or other unpleasant sensations. It is generally used in the following situations:

- Procedures that involve significant pain or unpleasant sensations, such as surgery, dental scaling and extractions.

- The animal is nervous or uncooperative and is required to remain very still for procedures such as X-rays, MRI, CT scans.

- Occasionally for ear cleaning (especially if the ears are very badly infected).

- To manage repetitive, uncontrollable seizures or heavy breathing leading to collapse of the windpipe.

Key factors that affect anaesthesia risk

- Nature of procedure: Invasive procedures (open surgery) carry a higher risk than non-invasive procedures (e.g. dental cleaning).

- Length of procedure: The longer the procedure, the higher the risk.

- Age: The older the animal, the greater the anaesthetic risk because there may be pre-existing conditions of the heart, lung, liver or kidney. Animals below 1 year of age have a slightly higher anaesthesia risk as their organs may not be fully developed.

- Health status: The healthier the animal, the lower the anaesthetic risk. Animals with pre-existing health problems (such as heart conditions) face greater anaesthetic risk.

- Breed: Brachycephalic (flat-faced) breeds such as the Pug, Bulldog, Pekingese have structural problems with the nasopharynx which make breathing more difficult when they are asleep and completely relaxed.

What can be done to minimise the risk?

1. Pre-anaesthetic exam and blood tests

A thorough medical history provides valuable information about your pet’s health. Physical exam may reveal abnormalities of the heart or lungs which may require further evaluation such as an electrocardiogram, chest X-rays or ultrasound prior to surgery. Pre-anaesthetic blood tests are important to check blood glucose, kidney and liver function and screen for pre-existing health issues, especially in older pets.

- Complete blood count: To ensure there is no ongoing infection and to check the level of red blood cells and platelets, which are important in blood clotting.

- Kidney & liver function tests: The kidney and liver are organs which process the anaesthetic drugs, so it is important they are functioning properly.

- Heartworm & tick fever tests: Heartworm, which may not be detected on physical examination in early stages, can affect the heart’s ability to withstand stress, especially during surgery. Tick fever can affect blood clotting, which will greatly increase the amount of blood loss during surgery.

2. Intravenous fluids

For older animals with a higher anaesthesia risk or undergoing longer procedures, your vet may include intravenous (IV) drip to help your pet maintain hydration and blood pressure, process anaesthetic drugs faster and provide a convenient route for vets to administer fluids and medication into the bloodstream.

3. Airway intubation

A soft plastic tube (endotracheal or ET tube) is inserted into the windpipe to maintain the airway for breathing. This is connected to an anaesthesia machine that delivers an inhalant anaesthetic in oxygen. It allows our vet to assist or control breathing if it becomes necessary.

* Fasting your pet for several hours prior to anaesthesia (as directed by your vet) is important. A your pet who is not properly fasted could vomit during or shortly after being anaesthetised and possibly aspirate food or fluid into the lungs. Aspiration pneumonia can be life-threatening.

4. Anaesthetic monitoring

The number one cause of anaesthetic complications leading to death is cellular hypoxia – cells are starved of oxygen. Our patient’s vital signs such as heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, blood oxygenation are continuously monitored throughout the anaesthetic procedure.

Staying warm during and after surgery

Patients often experience hypothermia (reduced body temperature) during anaesthesia. Body temperature may be further reduced with the use of intravenous fluids, clipping of fur and surgical preparation. Warming pads are routinely used during anaesthesia to keep our patients warm. Anaesthetic monitoring constantly measures the body temperature during surgery.

Pain management – rest better and recover faster

Pain management is crucial as it alleviates discomfort and helps our animals recover faster. Pain relief medication is usually administered before, during and after surgery. This helps reduce stress and pain associated with surgery, allowing the animal to rest better and recover faster. It is always better to start on pre-emptive analgesia than to control pain once it has started.

With appropriate pre-anaesthesia examination, careful monitoring and competent after-care, the risks of anaesthesia can be minimised. Most animals are back to their normal selves within 12 to 24 hours. If your pet does not fully recover from the anaesthetic by the following day, contact your vet immediately.

Dr Kasey Tan, Mount Pleasant Animal Clinic (North)